Downwind Wine: Issue #11

Weather windows, interdependence, thresholds, and a "six challenges" tool

Weather Window

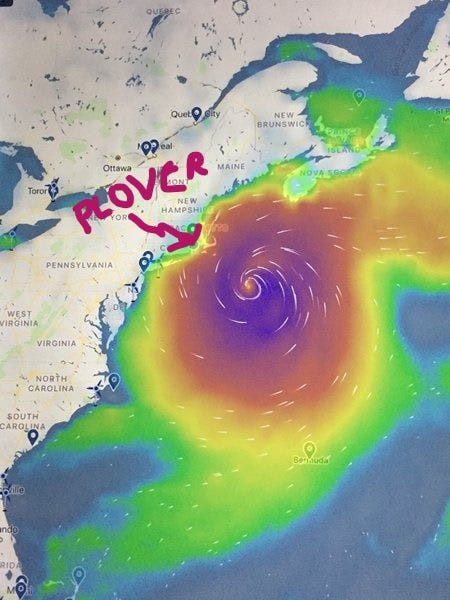

In 2019 my cousin and her husband invited me to do an offshore passage back to the US from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on their sailboat Plover. I made reservations to fly up, planning to meet them somewhere along the coast and sail for 10 days or so. And then I got the phone call: “There’s a storm coming up the East coast. There’s a small weather window for departure. You need to get here tomorrow.” I landed in Halifax just before midnight, and took a taxi to the small marina where they were docked. I crept aboard, found my bunk, and got a little sleep. As dawn was breaking we cast off and headed out.

Some time I’ll write about being offshore, away from the lights of land, but I'll fast forward a few days. We made our way to the New England coast, with Hurricane Dorian heading up to meet us. We anchored in an inland harbor and bundled up the boat, and the storm passed on by. I enjoyed a few more days on the boat and flew home from New York.

Chris & Bill needed to get home from Halifax before winter set in, and had a initial plan for when they would leave, but the storm pushed them to make their best guess about what conditions would be like several days ahead, pick their timing, and go. They subscribed to a weather service that helped them forecast what winds and currents would be like along their route. And then they had to adjust the plan based on emerging conditions. If I hadn’t been prepared to accelerate my travel plans and live with some uncertainty about when, and from where, I would head home, I would have missed the whole thing!

Questions for Reflection: What situations can you think of where you recognized a “weather window” in your life that required you to move more quickly—or more slowly—than planned? When you see stormy weather headed your way, how do you go about adjusting your plans, finding a safe harbor, and continuing on once the coast is clear?

On the Water

Building Synergy: Interdependence

This is the third installment in my exploration of the framework for building synergy. I have talked about variety (DWW#3) and common goals (DWW#6) as two prerequisites for synergy. Today I’m going to tackle interdependence: recognizing when successful outcomes require collaborating with people who bring different perspectives. I’ve been losing some sleep over this one, because in many ways it is the crux of the challenge. No matter how much people may agree about the goals they’d like to achieve, they won’t put in the effort to work with each other—especially when the going gets tough—unless they have a reason.

Collaboration is not always my first move. I’m pretty independent, and I like to figure things out for myself. Many people I know are the same way. Just because someone else thinks I should work with them doesn’t mean I’m willing to do it—it’s often a lot easier to do it myself.

I reflected on situations where I have experienced interdependence with others, and also on those where I have seen others follow through on a commitment to collaboration. In particular, I focused attention on places where people or groups with significant sources of tension and disagreement have successfully worked to create breakthrough solutions.

It seems to me that there are at least three general categories of motivation to commit to working interdependently with others.

Agreements and Contracts

When we enter an agreement with someone—a business partnership, a marriage, or some other formal contract, it can serve as a binding force that causes us to stay engaged in working through problems and disagreements. Contracts often include mechanisms for resolving issues—mediation, arbitration, etc.—and sometimes involve penalties for the failure to reach a resolution.

Situational Constraints

Sometimes interdependence is driven by factors in the situation that prevent us from achieving desired goals independently. These might include financial, economic, organizational, and practical constraints. For example, the U.S. Constitution requires that a certain number of senators and representatives support a bill before it becomes law. This often requires collaboration across party lines to pass important legislation.

One of my mentors, Daryl Conner, gives an example from his work in race relations in the Vietnam era—one instance in which black and white soldiers would work together is in a foxhole during a battle. When one person has the gun and the other has the bullets, and there’s an enemy trying to kill you both, there is a very strong motivation to cooperate.

I asked one of my AI colleagues to provide some examples of how organizational leaders might set up situational constraints to motivate people to work together. Here are a few examples:

Shared budget pool. No separate line items—groups draw from one pot. Overspending in one area means cuts elsewhere. This forces negotiation on priorities.

Joint P&L or combined metrics. Groups succeed or fail together on the same numbers. You can’t short-change or undermine someone else without hurting yourself.

Resource sharing. Provide one facility and set of equipment to be used by several teams. If you want access, you have to coordinate. Physical scarcity drives collaboration.

This reminded me of what my parents did when my siblings and I were younger. They set limits on the number of hours the TV was on, and we all had to agree on which shows we would watch. There was definitely some negotiation and compromise in figuring that out!

Moral/Spiritual Commitments

Ultimately, the most powerful reason for operating interdependently is the personal commitment to a belief, a relationship, a philosophy, or some other purpose that transcends the self. When Protestants and Catholics began to work together in Northern Ireland, it was because they were both committed to the hope of a better world. When I have worked to resolve issues in my marriage, it’s not because of any legal agreement, but because of my belief that the promise I made is sacred. When people embrace the “No About Us Without Us” philosophy as it relates to accessibility and inclusion, they take on a responsibility to involve everyone affected by decisions in the process.

Unlike legal agreements or situational constraints, these commitments must be held from within. This means that they can’t be legislated, engineered, or forced in any way. However, I believe that there is a lot that can be done to invite people to engage in collaboration around tough issues, difficult conversations, and challenging problems. This can include framing tough issues as shared responsibilities, highlighting common values, telling stories of people and groups who have worked to transcend their differences, articulating clear standards and expectations for ourselves and others, and, above all, leading by example and serving as role models for others.

Questions for Reflection: Where have you operated independently with someone else? Where have you chosen to commit to tough discussions when it might have been easier to walk away? What motivated you to do these things? How have you helped create situations in which others work collaboratively with people they might disagree with?

Thresholds

For some reason this passage from John O’Donohue (from To Bless the Space Between Us) called out to me at this season.

To change is one of the great dreams of every heart...So often we look back on patterns of behavior, the kind of decisions we make repeatedly and that have failed to serve us well, and we aim for a new and more successful path or way of living. But change is difficult for us. So often we opt to continue the old pattern, rather than risking the danger of difference. We are also often surprised by change that seems to arrive out of nowhere.

We find ourselves crossing some new threshold we had never anticipated. Like spring secretly at work within the heart of winter, below the surface of our lives huge changes are in fermentation. We never suspect a thing. Then when the grip of some long-enduring winter mentality begins to loosen, we find ourselves vulnerable to a flourish of possibility and we are suddenly negotiating the challenge of a threshold.At any time you can ask yourself: At which threshold am I now standing? At this time in my life, what am I leaving? Where am I about to enter? What is preventing me from crossing my next threshold? What gift would enable me to do it? A threshold is not a simple boundary; it is a frontier that divides two different territories, rhythms, and atmospheres. Indeed, it is a lovely testimony to the fullness and integrity of an experience or a stage of life that it intensifies toward the end into a real frontier that cannot be crossed without the heart being passionately engaged and woken up. At this threshold a great complexity of emotion comes alive: confusion, fear, excitement, sadness, hope. This is one of the reasons such vital crossings were always clothed in ritual. It is wise in your own life to be able to recognize and acknowledge the key thresholds: to take your time; to feel all the varieties of presence that accrue there; to listen inward with complete attention until you hear the inner voice calling you forward. The time has come to cross.

Here are a few images from my photo files that evoked a threshold theme for me.

Six Challenges: Now You Can Try It!

I’m working on applying my Prosilience framework (from this book) to specific sets of challenges that people or groups might face. For instance, what are some common challenges of people who manage volunteers in community organizations? Of nurses in rural hospitals? Of women leaders in technology? I believe that getting specific helps us do a better job of thinking through which resilience tools and strategies might be helpful.

So, in my continuing experimentations with AI, I worked with claude.ai to create a tool that allows you to specify a constituency (individual, group, etc.)—it then articulates six challenges and suggests linkages to the Prosilience building blocks. You can find it here, and plug in any subject you want. It will do the analysis and create a document you can download and do whatever you want with. It’s free, and you are welcome to share with others who might be interested. You do need to sign up for a free claude.ai subscription to use it. If you try it, let me know what you think!

I’ll close with this. Love the song, and the singer, and Martin Hayes is one of my favorite Irish fiddlers. See you in a few weeks!